Frida Kahlo: From the Shadow of Diego to the Light of the World

By Alex Mares | Anno Media

A new museum in Mexico City redefines how we see Frida Kahlo — the woman, the artist, and the myth.

When Frida Kahlo died in 1954, she was known more as the wife of Mexico’s most celebrated muralist, Diego Rivera, than as a major artist in her own right. Rivera was revered across the Americas, commissioned by governments, and adored by intellectuals. Frida, meanwhile, was admired in small circles — a curious, gifted painter of striking self-portraits filled with pain and passion, but far from the global icon she would later become.

Seventy years later, her face is everywhere — on tote bags, T-shirts, and museum walls from Tokyo to Paris. Her life story, filled with physical suffering and emotional resilience, has become universal shorthand for authenticity and strength. And now, as a third museum dedicated entirely to her life opens in Mexico City, the world once again returns to Frida — this time, to discover new layers behind the legend.

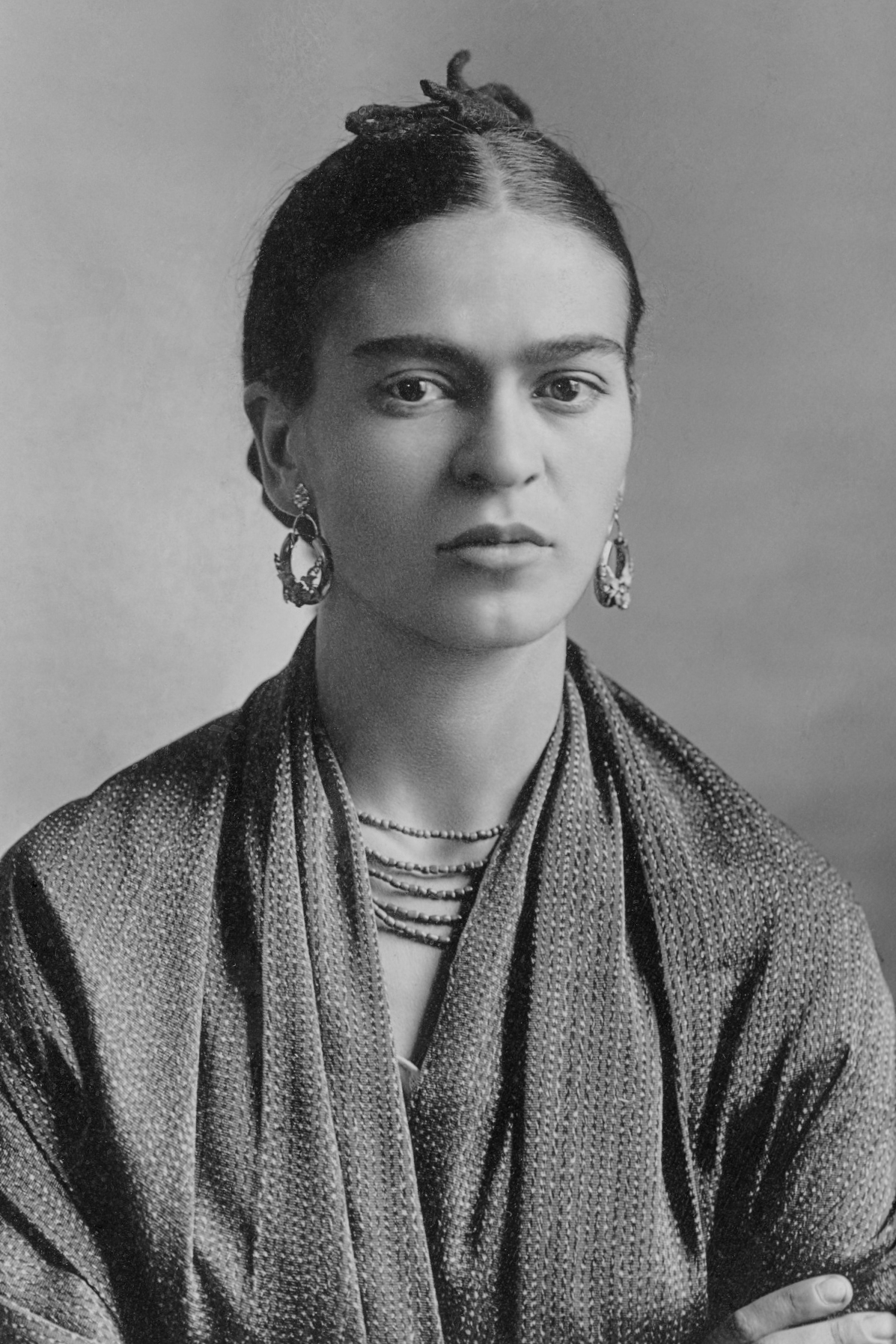

Frida Kahlo, by Guillermo Kahlo

The Girl from Coyoacán

Frida Kahlo was born in 1907 in the quiet suburb of Coyoacán, Mexico City, in a bright blue house that would later become her shrine. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was a photographer of German-Hungarian origin; her mother, Matilde Calderón, was of indigenous and Spanish descent. This mix of European and Mexican roots would later find vivid expression in her art.

At 18, a horrific bus accident changed her life forever. Bedridden for months, she began painting — first out of boredom, then out of necessity. Her works became a mirror of her soul: vivid, symbolic, brutally honest. Kahlo turned her body into a landscape of metaphors — thorns, roots, tears, bones — painting herself not out of vanity but out of survival.

“I paint myself because I am so often alone,” she once said, “and because I am the subject I know best.”

Diego’s Shadow

When she married Diego Rivera in 1929, their relationship shocked and fascinated everyone — the young, fragile Frida beside the massive, famous muralist twice her age. Their marriage was a storm of passion and betrayal, art and politics. He introduced her to the Mexican avant-garde, to Trotsky and Breton, to New York and Paris. But in the art world of their time, Diego’s murals spoke for Mexico; Frida’s small canvases were seen as personal curiosities.

When Frida died in 1954, her passing barely made international headlines. Rivera was still the titan of Mexican modernism. She was “Diego’s wife who also painted.”

He was the one who, paradoxically, secured her immortality. In his will, Rivera donated La Casa Azul, their beloved home in Coyoacán, to become the Museo Frida Kahlo. That act planted the first seed of her posthumous fame.

Kahlo with husband Diego Rivera in 1932 – By Carl Van Vechten

The Rise of Fridamania

It wasn’t until the 1970s that Frida Kahlo’s reputation truly began to grow. The feminist movement rediscovered her as a revolutionary woman who painted her body and pain without apology. Her bold embrace of indigenous Mexican culture, gender fluidity, and political idealism resonated with new generations seeking authenticity and identity.

In the 1980s, art historians began to reappraise her paintings as complex, coded works — surreal yet real, intimate yet universal. By the early 2000s, Frida was no longer just an artist; she was an icon. The 2002 film Frida starring Salma Hayek sealed her myth for the global audience.

Today, she stands among Picasso and Van Gogh as one of the most recognizable figures in art history. And unlike many artists of her time, she represents not a school or movement but a life lived in color, pain, and defiance.

A Third Museum for a Boundless Life

In 2025, Mexico City opened its third museum dedicated to Frida Kahlo — the Museo Casa Kahlo, or Casa Roja (“The Red House”).

Located just a few blocks from the famous Casa Azul, this new museum reveals another side of Frida: her childhood, her family, and her inner world.

Casa Roja occupies the former home of her sister Cristina Kahlo, lovingly restored and curated by Frida’s descendants. Visitors can wander through intimate rooms filled with personal letters, photographs, childhood drawings, and even the darkroom of her father, Guillermo. There are multimedia installations that bring her voice, diaries, and family stories to life.

While Casa Azul tells the story of Frida the artist and public figure, Casa Roja focuses on Frida the daughter, sister, and woman — before fame, before Diego, before myth.

“It’s about roots,” says one of the curators. “To understand Frida, you must understand the family and the house that shaped her.”

The three museums — Casa Azul, Casa Roja, and Casa Estudio Rivera-Kahlo — now form a unique cultural triangle in Mexico City, offering a complete portrait of an artist whose life defied boundaries.

La Casa Azul, which has been open to the public since 1958 as a museum dedicated to Frida Kahlo

Why the World Still Needs Frida

Why build yet another museum for an artist so omnipresent?

Because Kahlo’s story still speaks to us — perhaps more now than ever.

She lived through pain yet transformed it into beauty. She turned the private into the political, the personal into the universal. Her art refuses pity; it demands empathy. In an age of filtered perfection, Frida’s truth feels radical again.

Millions still queue to see her paintings not because they are technically perfect — but because they are human. They are self-portraits of endurance, of dignity, of the fragile miracle of living.

The Legacy Continues

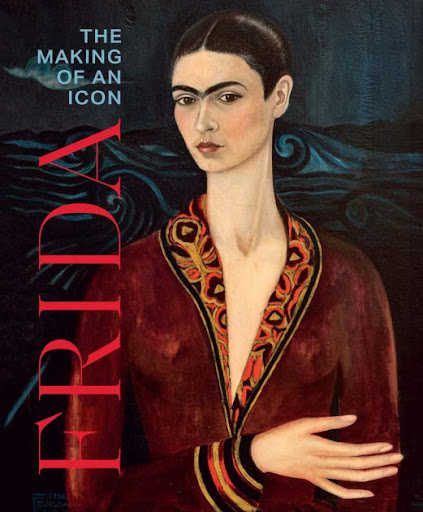

In 2026, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston will open “Frida: The Making of an Icon,” an exhibition tracing her transformation from overlooked painter to global symbol. It will later travel to London’s Tate Modern, continuing her dialogue with the world.

Meanwhile, in Mexico City, Casa Roja welcomes its first visitors — not to show a saint or a brand, but a woman. One who laughed, loved, painted, suffered, and dared to be entirely herself.

“I never paint dreams or nightmares,” Frida Kahlo once said. “I paint my own reality.”

And perhaps that is why the world keeps returning to her — because, in her reality, we find our own.