Medusa: From Terror to Beauty in World Art

Few mythological figures have fascinated artists as much as Medusa. With her serpent hair, petrifying gaze, and tragic backstory, she has been painted, sculpted, engraved, and reimagined for centuries. More than a monster, Medusa is an eternal mirror of human fears, desires, and changing ideals of beauty.

The Ancient Origins

In Greek mythology, Medusa was one of the three Gorgons, the only mortal among them. According to Hesiod, she lived at the edge of the world, beyond Oceanus. Later Roman poets such as Ovid gave her a more human tragedy: once a maiden of striking beauty, Medusa had been cursed by Athena after Poseidon violated her in the goddess’s temple. Her shimmering hair turned into serpents, and her gaze became lethal — whoever met her eyes turned into stone.

Perseus’ decapitation of Medusa, with Athena’s guidance, was celebrated as a heroic feat. Yet even in antiquity her image was paradoxical. The Gorgoneion, the severed head of Medusa, appeared on shields, temples, mosaics, and coins. Terrifying and grotesque, it served as an apotropaic symbol: horror transformed into protection. From the Parthenon to Alexander the Great’s armor, her face was both feared and revered.

By Godfried Maes – The Art Institute of Chicago

Renaissance Rebirth

The Renaissance rediscovered Medusa not as a demonic talisman but as a subject of artistic fascination. Benvenuto Cellini’s bronze “Perseus with the Head of Medusa” (1554), displayed under the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, embodies the triumph of humanist heroism. The youthful Perseus stands nude, elegant, almost godlike, raising the dripping head — Medusa’s agony immortalized in bronze.

Leonardo da Vinci was said to have painted a Medusa early in his career (though now lost), which Giorgio Vasari described with horror and admiration. In these works, the emphasis shifted: Medusa was not only a monster but also a study of anatomy, psychology, and emotion.

Baroque Drama: Caravaggio’s Medusa

No image of Medusa is more unforgettable than Caravaggio’s shield painting (1597), commissioned as a ceremonial gift for the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Painted on convex wood to resemble an actual shield, the work captures the exact instant of death: her eyes wide in shock, mouth frozen mid-scream, serpents twisting violently.

Caravaggio, a master of theatrical realism, gives Medusa a human dimension — we see not only terror but also the dignity of a creature caught between beauty and monstrosity.

Medusa (c. 1597), by Caravaggio

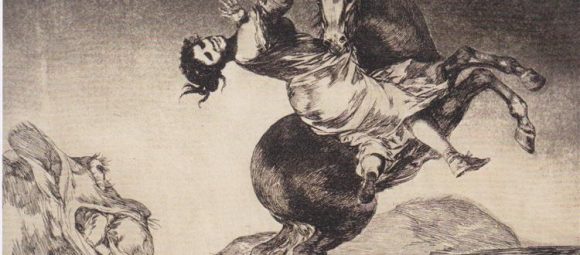

Romanticism and the Symbolists

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Medusa’s story had taken on new meanings. She was no longer only the monster to be slain but also the victim, the cursed beauty, the tragic figure.

Painters such as Peter Paul Rubens dramatized the severed head with grotesque snakes and dripping blood, turning horror into spectacle. Later, Arnold Böcklin portrayed her as sorrowful and introspective, her features still beautiful beneath the serpents. For Symbolists, she became a reflection of the subconscious: fear, temptation, and eroticism mingling in one image.

Medusa by Arnold Böcklin, c. 1878

Poets and writers also revived her: Shelley called her “beautiful and full of horror,” while the Romantics saw in her an allegory of forbidden desire.

Modern Transformations: From Femme Fatale to Feminist Icon

The 20th century pushed Medusa into new territory. Auguste Rodin sculpted her as sensual and anguished, merging fear with seduction. The Surrealists, fascinated by myth and dream, reimagined her serpents as metaphors for the unconscious mind.

Fashion and design appropriated her image: Versace adopted Medusa’s head as its logo, a symbol of allure, attraction, and power impossible to resist. Cinema too returned to her myth, from Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion Medusa in Clash of the Titans (1981) to countless modern reinterpretations in popular culture.

Today, Medusa has been claimed as a feminist symbol. Her story is reread not as divine punishment but as a tale of injustice: a woman punished for being a victim. Artists, writers, and activists reinterpret her petrifying gaze as one of defiance — a weapon against those who wronged her.

Eternal Allure

From archaic temples to Baroque canvases, from Romantic poetry to contemporary fashion, Medusa remains one of the most reproduced figures in world art. Her appeal lies in her contradictions: beauty and horror, fragility and strength, victim and avenger.

To gaze at Medusa is to confront the paradox of art itself: it can terrify and enchant, it can destroy and preserve, it can freeze a fleeting human emotion into an eternal image. Medusa reminds us that even in monstrosity, there is truth, and in tragedy, a form of beauty.