The Image of the Horse in World Art History

The Year of the Fire Horse invites us to return to one of the most powerful and enduring images in human culture. Across millennia, civilizations have turned to the horse to express energy, nobility, freedom, conquest, speed, devotion, and destiny. Few animals have been depicted so consistently—and so symbolically—across time, geography, and artistic languages.

This long-read traces the visual biography of the horse in world art: from sacred animal and cosmic force to instrument of empire, companion of heroes, and finally a symbol of inner power and modern freedom.

I. The First Horse: Magic, Survival, Spirit

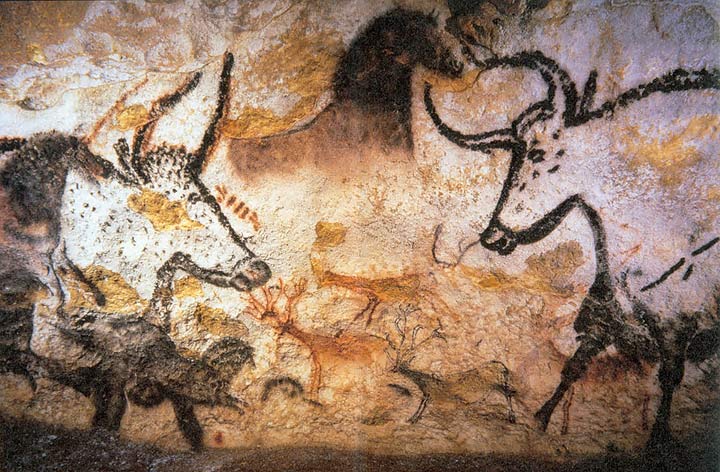

Aurochs, horses and deer painted on a cave

The earliest images of horses appear not in palaces or temples, but deep underground.

In Lascaux Cave and Chauvet Cave, horses gallop across stone walls with astonishing vitality. Painted more than 17,000 years ago, these animals are not decorative – they are animated presences, drawn with motion, tension, and rhythm.

For Paleolithic humans, the horse was:

Art historians often note that these horses are depicted more frequently than mammoths, suggesting not dominance, but fascination. The horse is already more than an animal –it is a power.

II. Antiquity: The Horse as Cosmic and Political Order

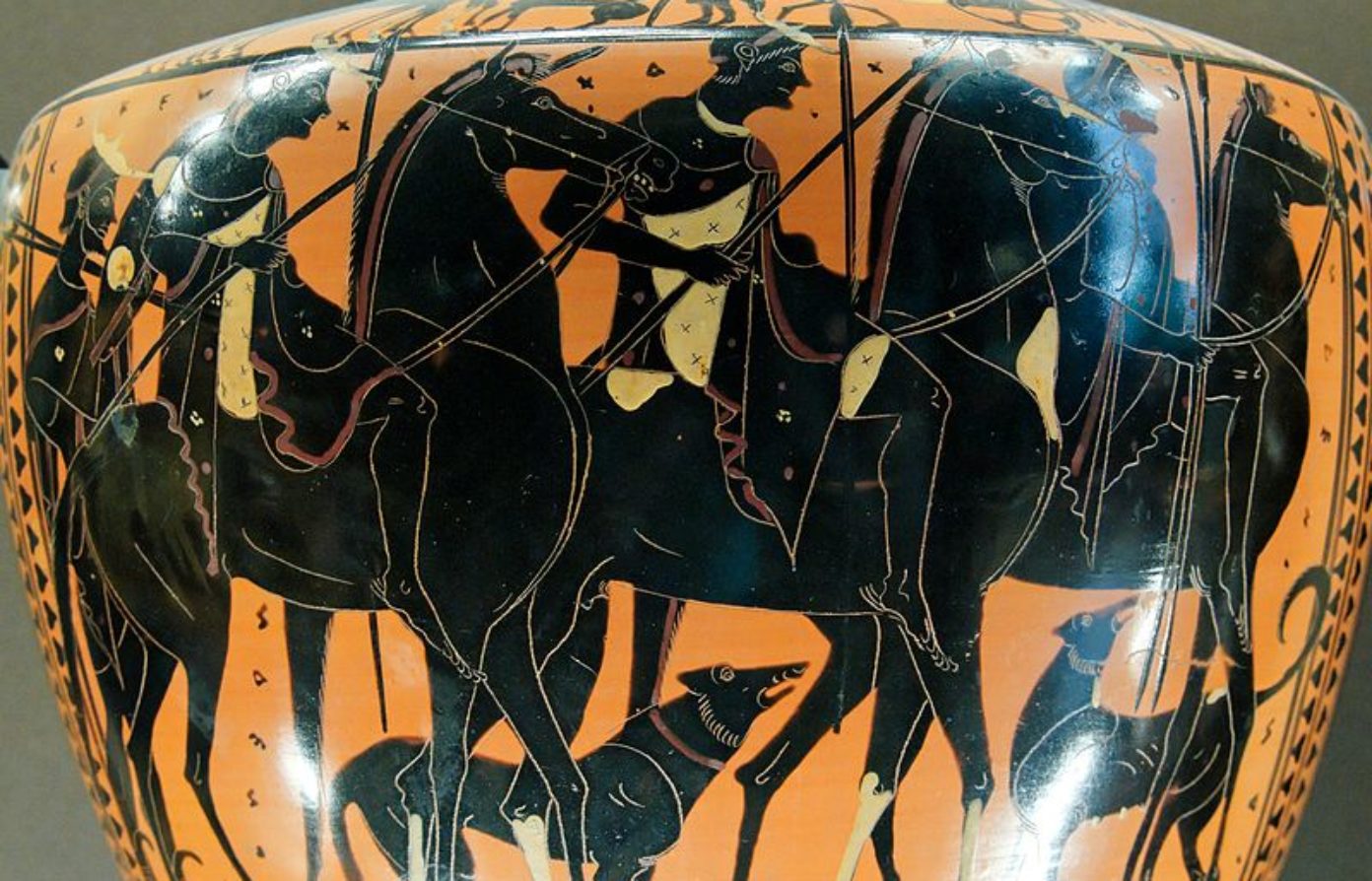

Riders and their dogs depicted on an ancient Greek vase c. 510-500 BC.

Greece: Harmony and Heroism

In ancient Greece, the horse embodied arete – excellence and balance.

The horse becomes inseparable from the hero:

Rome: Power Cast in Bronze

Rome monumentalized the horse in imperial imagery. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius survives not by chance, but because later generations mistook it for Constantine.

Here the horse symbolizes:

The rider rules the world—but only through mastery of the horse.

III. Asia: Sacred Strength and Heavenly Speed

Terracotta Army in Xi’an, China

China: The Heavenly Horse

In China, horses were associated with heaven, wind, and immortality.

The so-called “Heavenly Horses” from Ferghana were believed to sweat blood – a sign of divine origin.

Islamic & Mughal Worlds: The Noble Companion

In Persian and Mughal miniature painting, horses are:

In works illustrating the Shahnameh, the horse is a moral being – loyal, brave, intelligent.

IV. The Middle Ages: Apocalypse and Chivalry

Medieval people engaging in falconry from horseback. The horses appear to have the body type of palfreys or jennets from the Codex Manesse

Medieval Europe split the image of the horse into two symbolic extremes.

The Sacred and the Terrifying

In Apocalypse imagery, horses carry the Four Horsemen – war, famine, plague, death. Color becomes meaning.

The Knight’s Mirror

At the same time, the knight and horse form a single moral unit:

Saint George’s horse is as virtuous as the saint himself.

V. Renaissance & Baroque: Anatomy, Power, Theatre

Benozzo Gozzoli, The fresco on the eastern wall of the Magi Chapelё in Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, 1459

The Renaissance rediscovered the horse as a scientific marvel.

In the Baroque:

The horse becomes theatre: muscle, sweat, rearing movement frozen in oil paint.

VI. Romanticism: The Horse Unbound

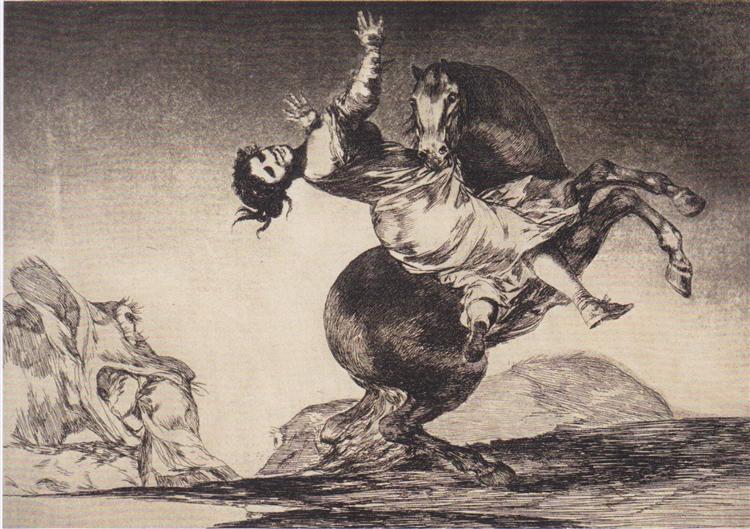

Abducting horse by Francisco Goya

Romanticism freed the horse from kings.

The horse now mirrors the human psyche.

VII. Modernity: Speed, Memory, Loss

Horse Head. Sketch for “Guernica” by Pablo Picasso (1937)

The 20th century shattered the classical horse.

The horse survives modernity not as power—but as remembrance.

VIII. The Fire Horse Today

The Fire Horse unites contradictions:

In contemporary art, photography, cinema, and performance, the horse often appears without a rider. It stands alone – an echo of humanity’s long partnership with nature.

Perhaps this is the ultimate meaning of the Fire Horse: not domination, but energy without chains.