Why the Lion? Origins of the Symbol

The lion became the symbol of Venice through its association with Saint Mark the Evangelist, the city’s patron saint. According to legend, while traveling through the lagoon, Venetian merchants stole the relics of Saint Mark from Alexandria in 828 AD. They concealed the saint’s remains under layers of pork to avoid detection by Muslim customs officers. Upon returning to Venice, the relics were housed in a newly built basilica — now the iconic St. Mark’s Basilica.

The lion was already a known symbol of Saint Mark in Christian iconography — especially the winged lion, representing courage, power, and the evangelist’s divine inspiration. It often holds a book with the Latin phrase:

“Pax tibi Marce, evangelista meus” (“Peace be upon you, Mark, my evangelist”).

Symbolism and Power

The winged lion symbolized:

• Spiritual authority through the book.

• Temporal power when the lion appears with a sword (often during wartime).

• Protection of the Republic, appearing on coins, city gates, ships, banners, and state documents.

It was a visual assertion of Venice’s religious legitimacy and maritime dominance.

The Lion in Art: Sculptures, Paintings, and More

Venice’s artists and craftsmen incorporated the lion into nearly every medium:

Sculptures and Reliefs

• Piazza San Marco: The most iconic lion sculpture is the bronze Lion of Saint Mark atop one of the two columns in Piazzetta San Marco, dating to the 12th century (likely Hellenistic in origin, later restored).

• Arches and buildings: Lions grace the Doge’s Palace, city gates (like Arsenale’sentrance), and churches throughout the Republic’s vast territory — from Venice to Crete and Dalmatia.

• Tombstones and wells: Lions appear on private monuments and civic fountains.

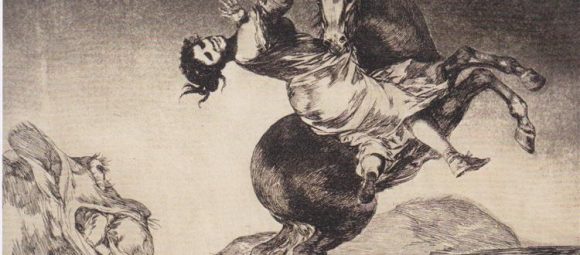

Paintings

• Gentile Bellini, Carpaccio, and other Renaissance masters included lions in narrative works — especially in paintings depicting miracles of Saint Mark.

• The lion was used to frame allegories of justice, wisdom, and strength, especially in governmental halls like the Sala del Maggior Consiglio.

Manuscripts and Coins

• Venetian illuminations feature lions in the margins or as page headers.

• Lions adorned ducats and silver coins, asserting the Republic’s prestige.

Lions Beyond Venice

The lion spread with Venice’s colonial reach:

• Crete (Candia): Venetian lions are carved into fortresses and fountains, like the Morosini Fountain in Heraklion.

• Istria and Dalmatian Coast: Towns such as Kotor, Zadar, and Split feature lion reliefs.

• Cyprus, Corfu, and the Peloponnese: All preserve remnants of Venetian lions on citadels.

These lions often carry regional adaptations, sometimes merged with local styles or inscriptions in Greek and Latin.

Where to Find the Lion Today

• Museo Correr (Venice): Holds sketches, standards, and artifacts with lion motifs.

• Doge’s Palace: A trove of lion imagery in paintings, sculpture, and architectural detail.

• St. Mark’s Basilica: Beyond the relics, it features golden mosaics and capitals with lions.

• Accademia Galleries: Paintings of Saint Mark and city allegories abound.

• Museums abroad: Fragments and paintings showing the Lion of Saint Mark appear in museums from the Louvre to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Legacy in Contemporary Venice

The lion remains ubiquitous in modern Venice:

• As part of the Venetian flag, fluttering during celebrations.

• In Biennale installations, especially in the Golden Lion Award (symbolizing artistic excellence).

• Used by local artisans for Murano glass, masks, jewelry, and textiles.

Conclusion

The Lion of Saint Mark is more than a symbol — it is Venice itself, immortalized in stone, bronze, pigment, and legend. It speaks of empire, spirituality, artistry, and endurance. No visit to Venice is complete without encountering this eternal guardian — from the glint of a museum sculpture to the shadow it casts across the Grand Canal.