Baron Haussmann and the Grand Transformation of Paris in the 19th Century

By Yana Ilyukhina | ANNO Media

In the second half of the 19th century, Paris underwent one of the most extensive and radical transformations in its history. This profound reconstruction, known as “Haussmannization” after its chief architect and organizer – Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann – forever changed the city’s appearance and turned it into a modern European metropolis.

Who Was Baron Haussmann?

Georges-Eugène Haussmann was a man of extraordinary energy and iron will. Originally from Alsace, with German roots, he was devoted to the Bonaparte dynasty from a young age – his father and grandfather served the emperor. Haussmann was broad-minded: he studied law, was passionate about music, and interested in architecture. But it was his determination and integrity – rare qualities for an official at that time – that attracted the attention of Minister of the Interior Victor de Persigny and Emperor Napoleon III himself. In 1853, Haussmann was appointed prefect of the Seine department, effectively becoming the administrator of Paris.

Henri Lehmann-Portrait du baron Haussmann

Goals and Objectives of the Reconstruction

Haussmann came to power at a time when Paris was desperately in need of change. By the mid-19th century, the population had grown to one million, and the old neighborhoods were overcrowded, narrow, filthy, and unsafe. The medieval streets could no longer handle the traffic and crowds, and there was no proper sewage or water supply system. Epidemics and high crime rates were common. Napoleon III, inspired by London’s architecture and urban planning, dreamed of transforming Paris into a city of wide streets, beautiful buildings, and green parks. He saw Haussmann as the man who could realize this vision.

Demolition of Old Districts and Construction of New Ones

Haussmann’s work began in preparation for the 1855 World’s Fair. As part of the reconstruction, he was granted unprecedented authority to demolish old districts without court procedures, which sparked much controversy. Slums around Place de la Bastille, one of the poorest and most rebellious areas, were destroyed. The old district of d’Arcis disappeared entirely, making way for the extension of Rue de Rivoli. Around Île de la Cité, many medieval buildings were demolished and replaced with the Palais de Justice, which includes the Conciergerie prison and Sainte-Chapelle chapel.

Rue de Rivoli became one of the first streets Haussmann widened and brightened. Perpendicular to it were the newly created Boulevard de Strasbourg and Boulevard de Sébastopol, formerly parts of defensive fortifications, now beloved promenades for Parisians.

Rue Jardinet, which was demolished to make way for the construction of Boulevard Saint-Germain. 1853–1870

State Library of Victoria

Development of Urban Infrastructure

Haussmann paid attention not only to the city’s appearance but also to its infrastructure. One of his key achievements was the world’s largest sewage system of that time, built by engineer Eugène Belgrand. This drastically improved sanitation and reduced disease. Additionally, Haussmann collaborated with financiers such as the Pereire brothers, who invested heavily in railways around Paris. The city also saw the introduction of public transportation – the omnibuses – making it easier to get around.

New Symbols of Paris

During Haussmann’s tenure, iconic architectural landmarks emerged, becoming symbols of Paris. The Palais Garnier opera house was built – a grand building richly decorated and considered an architectural masterpiece. The Gare du Nord and the Palais de l’Industrie on the Champ de Mars, constructed for the 1867 World’s Fair, also appeared.

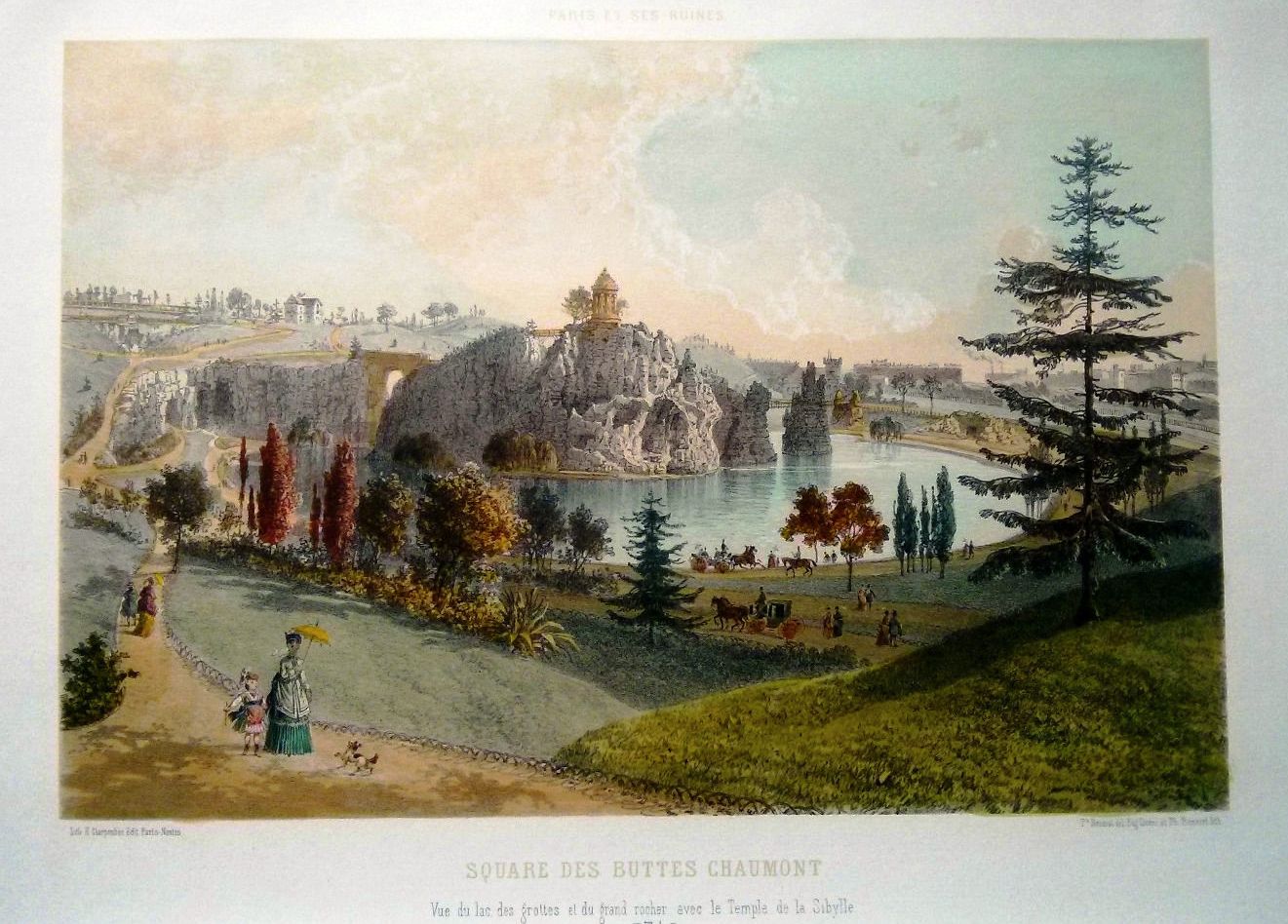

Green spaces were another focus: Parc Monceau and Parc des Buttes-Chaumont were created, alongside the preservation and improvement of the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forests. Each of the city’s 20 districts gained squares and small parks, enhancing urban comfort.

Park of Buttes Chaumont in 1871.

Social Consequences and Criticism

Despite great achievements, the reconstruction caused social tensions. The new apartments on wide boulevards were expensive, with landlords often charging rents that forced workers to spend most of their wages on housing. Old working-class neighborhoods were ruthlessly demolished.

Writers and public figures criticized the transformation. Victor Hugo accused Haussmann of “expelling poetry from Paris.” Émile Zola believed the reconstruction “cut the living city into pieces.” Architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc lamented the loss of historic monuments, including a Roman amphitheater that was paved over. Haussmann himself remained incorruptible — he refused large kickbacks and ensured project transparency.

Financial and Political Challenges

The reconstruction was enormously costly – initial budgets were quickly exceeded, and Haussmann had to request additional funding. Total expenses surpassed 400 million gold francs, including compensation for owners of demolished properties.

In 1870, amidst growing political tensions and dissatisfaction, Haussmann was dismissed. Napoleon III was soon captured in the Franco-Prussian War, and Paris experienced the turbulent Commune uprising.

Haussmann’s Legacy in Modern Paris

Although initially criticized, Haussmann’s transformation has become an inseparable part of Paris’s character. Today, it is impossible to imagine the city without its wide boulevards like Boulevard Haussmann, the majestic Palais Garnier, the grand train stations, and well-maintained parks. His renovation made Paris safer and more comfortable, turning it into a magnet for millions of residents and tourists.

Baron Haussmann remains in history as the man who radically changed Paris – not without controversy, but with an enormous contribution to the city’s development, laying the foundation for its future prosperity.