Elysium: From Ancient Paradise to Modern Dreams

By Dmitri Yusov | ANNO Media

Elysium — or the Elysian Fields — has been one of humanity’s most enduring visions of paradise. First evoked in the poetry of Homer, the concept traveled through centuries of myth, philosophy, and art, leaving traces not only in Greek epic but also in Parisian boulevards and even in modern music.

Homer’s Isles of the Blessed

The earliest surviving description of Elysium comes from Homer’s Odyssey. In Book IV, the sea-god Proteus tells Menelaus, husband of Helen, that because of his kinship to Zeus he will not die, but instead dwell in the Elysian plain:

“For you it is not appointed to die in Argos,

but the deathless ones will send you to the Elysian plain,

at the ends of the earth, where life is easiest for men:

no snow is there, nor heavy storm, nor ever any rain,

but always the Ocean sends up breezes of the West Wind

blowing cool for the refreshment of men.”

(Odyssey IV, 561–568, transl. A.T. Murray)

Unlike the shadowy Hades, Elysium offered a vision of reward: a place where the noble dead could live in harmony, surrounded by light and beauty. Hesiod and Pindar expanded the idea, while philosophers such as Plato imagined Elysium as the destination for just souls — a bridge between myth and morality.

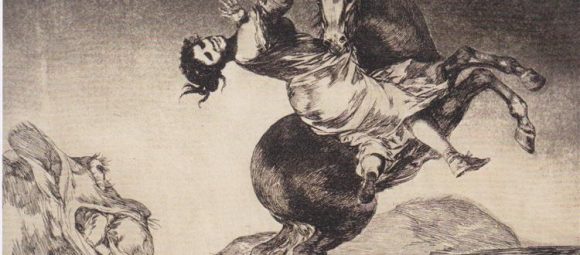

Elysian Fields by Carlos Schwabe, 1903

From Myth to Metaphor

In Roman times, Virgil placed Elysium in the Aeneid, describing shining fields where poets, warriors, and lovers strolled in eternal spring. Later, Dante’s Divine Comedy drew on similar imagery when evoking his earthly paradise atop Mount Purgatory. Shakespeare invoked “Elysium” in Twelfth Night and Henry V as a poetic synonym for bliss.

Artists, too, found inspiration: Nicolas Poussin’s classical landscapes often hinted at Elysian calm, while 19th-century Romantic painters such as John Martin imagined luminous afterworlds echoing the ancient paradise. In the 20th century, the Surrealists turned Elysium into a dreamscape, where the boundary between real and unreal dissolved.

On Stage and Screen

Elysium’s appeal extended into modern culture. Jean Anouilh named his 1940 play Eurydice “a modern myth for an Elysium in the railway café.” In cinema, Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) made perhaps the most moving use of the idea: the general Maximus dreams of walking again through wheat fields toward his family, an unmistakable echo of Virgil’s Elysium. Later, Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium (2013) reimagined the concept as a futuristic orbital paradise for the privileged few, contrasting Earth’s suffering with an unreachable heaven.

Even in music, the name appears again and again — from Mozart’s references in his operas to Joe Dassin’s chanson.

The Champs-Élysées: Paradise in Paris

This ancient concept even made its way into urban geography. In Paris, the Champs-Élysées — literally the “Elysian Fields” — was laid out in the 17th century as a tree-lined promenade extending westward from the Tuileries. By the 19th century, it had become the most famous avenue of the French capital, a symbol of elegance, leisure, and modern life.

To stroll along the Champs-Élysées was, in a sense, to walk in paradise on earth. For Parisians and visitors alike, the name infused the urban experience with classical echoes, turning a street into a metaphorical garden of delight.

Joe Dassin’s Eternal Song

The resonance of the Elysian Fields did not end with classical scholars or city planners. In 1969, the French-American singer Joe Dassin recorded his iconic song Les Champs-Élysées. Its joyful refrain — “Aux Champs-Élysées, au soleil, sous la pluie, à midi ou à minuit…” — celebrated the avenue as a place where anything could happen: encounters, love stories, the essence of Parisian joie de vivre.

Here, Elysium is no longer an unreachable paradise but a tangible boulevard, where daily life itself can feel eternal.

A Timeless Idea

From Homer’s poetry to Shakespeare’s stage, from Virgil’s golden fields to Hollywood’s wide screens, and from Paris’s grand boulevard to Joe Dassin’s chanson, Elysium has evolved but never disappeared. It remains a symbol of humanity’s longing for beauty, peace, and a world beyond suffering — whether imagined as a mythic plain, a shining city street, or simply the joy of a fleeting moment.

Elysium, then, is both a place and a dream — a reminder that paradise is as much about imagination as it is about geography.