Extraordinary Encounters and Extraordinary Destinies

Dmitri Yusov

Today, I would like to tell the story of an unusual couple and of encounters that were anything but accidental.

Let us meet Rukmini Devi Arundale and George Arundale.

He was English; she was Indian. They married in India in 1920, when she was sixteen and he was forty-two. The scandal was enormous. They became close friends with Anna Pavlova and Maria Montessori. Rukmini Devi nearly became President of India, yet she is best remembered for reviving the classical Indian dance form Bharatanatyam.

How did all of this happen?

Let us begin with George. He was born in 1878 into an aristocratic family, lost his parents early, and was adopted and raised by his aunt, a wealthy, unmarried woman and a devoted follower of the Theosophical movement. The Theosophical movement had been founded in the late 1870s by Helena Blavatsky. Theosophy quickly gained popularity in Europe and the United States, combining Western philosophy with Hindu and Buddhist ideas.

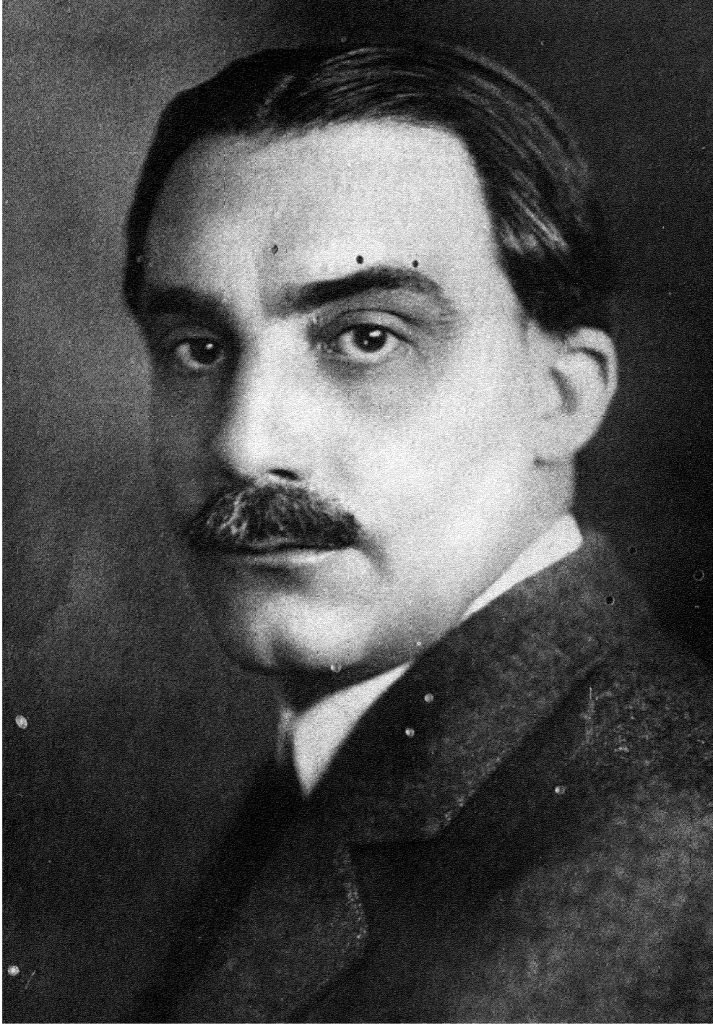

George Arundale c. 1903-13, as principal of Hindu College, Benaras

In an era of rapid technological progress and Darwinism, with its denial of God, Western intellectual circles discovered in Theosophy a form of Eastern spirituality that did not require abandoning their own cultural identity. Remarkably, Theosophy also found wide acceptance in India itself, among educated Indian elites. It returned Hinduism to Indians in a modern form respected by the West (under British rule, Hinduism had become somewhat marginalized). Moreover, Theosophy encouraged women to assert themselves — to lecture, to lead, to be independent. For the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this was revolutionary.

George grew up in this environment. After graduating from Cambridge, he and his aunt moved to India, immersing themselves in the work of the Theosophical Society, including its educational initiatives. George became a teacher and later the director of Benares University (today one of India’s most prestigious universities).

Rukmini was born on the rare date of February 29, 1904, into a Brahmin family. Her father was an engineer and a scholar. Inspired by the ideas and activities of the Theosophical movement, he relocated after retirement to Adyar (Chennai), where the headquarters of the Theosophical Society were located. As a result, Rukmini grew up in a highly distinctive intellectual and spiritual atmosphere.

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Her acquaintance with George developed into love and marriage. After their wedding, they traveled widely, meeting Theosophists around the world, and became friends with Maria Montessori, whose educational method was already being introduced in various countries.

By a twist of fate, they attended a performance by Anna Pavlova and her company in Bombay in 1928. They managed to meet her afterward, and later found themselves traveling on the same ship from Calcutta to Australia, where Pavlova’s troupe was touring. During the voyage, the Arundales and Pavlova grew close. Rukmini expressed a desire to study ballet. Pavlova encouraged her despite the fact that Rukmini was already twenty-five and gave her the first lessons herself, and asked one of her leading dancers, Cleo Nordi, to continue teaching Rukmini in Australia and later in London.

Yet Pavlova also advised Rukmini to seek inspiration in India’s own classical dance traditions, which by that time had nearly vanished. Rukmini took Pavlova’s advice seriously and began studying, practicing, and popularizing Bharatanatyam. Her goal was not only to revive a fading dance form, but also to overcome the powerful social stigmas attached to it.

Sri Rukmani Devi, October 6, 1940.

At the time, Bharatanatyam was effectively forbidden to most Indian women, as its traditional female performers had been exclusively devadasis women ritually “dedicated” to lifelong service in temples, usually from lower castes. After completing formal (and largely secret) training under an elderly master, Rukmini gave her first public performance in 1935 at the Theosophical Society, before an audience of one thousand people.

This performance set a precedent (initially perceived as yet another scandal) allowing Indian women to study and perform a dance form previously reserved for the devadasi community. But the beauty and purity of her dancing, combined with her personal charisma, led to a complete and lasting transformation of public perception. Her performance was hailed as “opening a new era in the history of modern Indian art.”

Only a week later, inspired by this moment, Rukmini, George, and several friends founded an academy of dance and music. Soon afterward, it was given the Indian name Kalakshetra, meaning “Sacred Place of Art.” Rukmini invited elderly dance masters and great musicians to teach the next generation, preserving priceless ancient traditions. Kalakshetra exists to this day, its campus covering forty hectares.

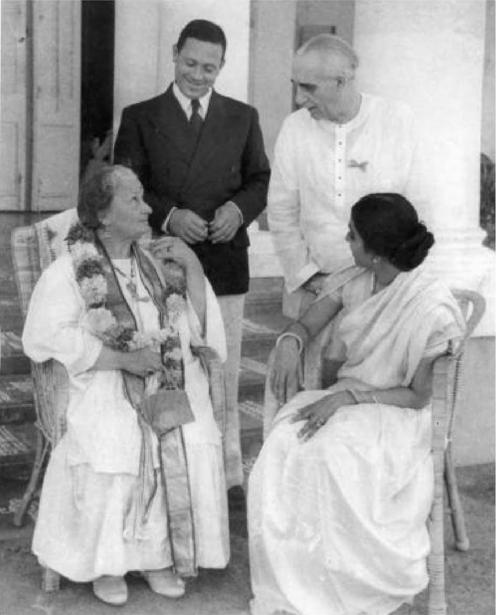

In 1939, George and Rukmini invited Maria Montessori to India for several months to give what we would now call a series of master classes and lectures across the country. Montessori arrived with her son Mario, who assisted her and later continued her work. When Italy entered the Second World War on Germany’s side, Britain interned all Italians under its control. Maria herself was spared, as she resided on the territory of the Theosophical Society; Mario was released after several months and reunited with his mother.

George, Rukmini and Maria Montessori with son Mario

They remained in Chennai until 1946, occasionally receiving permission to travel to other cities for lectures and workshops. During these years, Montessori’s influence on Indian school pedagogy was immense, though India, of course, also profoundly influenced the Montessori family.

George died in August 1945. The couple had no children. In the decades that followed, Rukmini became one of India’s most celebrated dancers and a central figure in the revival of Indian classical dance and music.

In 1952, she was nominated to the Upper House of Parliament for her outstanding achievements in the arts and her service to Indian culture, becoming the first woman in Indian history to hold such a position. She was nominated for a second term and traveled to Delhi for parliamentary sessions over a period of ten years, becoming known for her forthright speeches, especially on issues concerning women, children, and animal welfare.

In 1977, India’s Prime Minister Morarji Desai asked Rukmini Devi whether she would agree to become president. Legend has it that she replied with a question: “President of what?” “President of India,” the Prime minister answered. Rukmini declined the offer, choosing instead to continue the work at Kalakshetra that was so dear to her heart.

Rukmini passed away in August 1986, leaving behind an immense legacy. Over the decades, she became an ambassador of Indian culture, carrying the spiritual message of Indian dance and music around the world.

Extraordinary encounters and extraordinary destinies.