The Generation of ’27: Spain’s Lost Constellation

Most readers have heard of Federico García Lorca. Few know he belonged to a circle so brilliant that, had history been kinder, it might today stand alongside the Bloomsbury Group or the Russian Silver Age.

This is the story of Spain’s Generation of ’27 (Generación 27 in Spanish) a constellation of poets who tried to reconcile tradition and revolution, only to be torn apart by civil war.

Why “’27”?

In 1927, a group of young writers gathered in Seville to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Baroque master Luis de Góngora. Góngora had long been considered obscure, excessive, too ornate. These young poets believed the opposite: that Spain’s future lay in rediscovering the daring complexity of its past. The homage became symbolic. A date turned into a generation.

Sculpture in Torremolinos featuring some artists from the Generation of ’27 – Por Rafax – Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 4.0

Madrid Before the Storm

To understand them, imagine Madrid in the 1920s with cafés filled with debate, journals circulating new manifestos, evenings of poetry and piano. At the center stood the Residencia de Estudiantes, a laboratory of ideas where literature met science and painting. Here, Surrealism arrived. So did Freud. So did European modernity. Spain, often perceived as peripheral, suddenly felt at the very heart of cultural experimentation.

Beyond Lorca: The Other Voices

Lorca may be the most internationally known, but he was one among many distinct and powerful voices:

They were not stylistically uniform. Some wrote strict sonnets. Others broke syntax apart. What united them was the conviction that poetry could be both rooted in tradition and radically modern.

- Pedro Salinas

- Luis Cernuda

- Jorge Guillén

- Federico García Lorca

- Rafael Alberti

- Dámaso Alonso

- Vicente Aleixandre

Women of the Generation: The Silenced Half

For decades, the story of the Generation of ’27 was told almost exclusively through male names. Yet women were not peripheral to this movement, they were part of its very fabric.

Among them:

- Ernestina de Champourcín

- Concha Méndez

- Maruja Mallo

- Rosa Chacel

- María Zambrano

Some of them later became associated with the symbolic label Las Sinsombrero (“The Hatless Ones”) women who challenged social conventions as boldly as they challenged literary forms.

Why were they forgotten?

Civil War.

Exile.

Francoist conservatism.

And the simple inertia of a male-written canon.

Today, restoring their names is not an act of revisionism — it is an act of completion.

Tradition Meets Avant-Garde

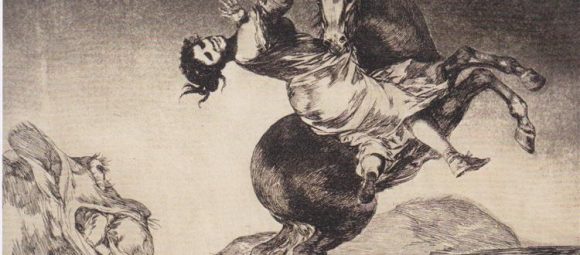

What made the Generation of ’27 exceptional was synthesis. They admired Góngoraand embraced Surrealism. They could write a flawless sonnet and a free-verse experiment. They were deeply Spanish, yet fully European. This balance between folklore and abstraction, ritual and rebellion, defines their enduring power.

The Fracture: 1936

Then came the Spanish Civil War. Lorca was executed in 1936.

Many others, men and women alike, went into exile: Mexico, Argentina, the United States. Those who remained faced censorship or internal silence. The generation dissolved not through aesthetic disagreement, but through political violence. Spain lost not just poets, but a possible cultural future.

Why They Matter Today

The Generation of ’27 reminds us that culture flourishes in openness and fractures under authoritarian pressure. Their story is not only Spanish. It is European. It is universal. A brilliant artistic moment. An interrupted modernity. A constellation only fully visible once it had scattered across the world.

For those who care about archives, exhibitions, and cultural diplomacy (like us at Anno Media), the Generation of ’27 feels deeply contemporary. It teaches us that artistic movements are ecosystems that are fragile, interconnected, dependent on freedom, and that sometimes, the task of our generation is simple: to remember completely.