The Quest for a Universal Language: From Babel to English

“And the Lord said, ‘Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.’”

— Genesis 11:7

The Tower of Babel: Humanity’s First Language Divide

The longing for a universal language is ancient and symbolic. According to the Book of Genesis, humanity once shared a single tongue. With growing ambition, they sought to build a tower that reached the heavens. Offended by this collective pride, God disrupted their unity by multiplying their languages and scattering them across the earth. The myth of the Tower of Babel became a metaphor for miscommunication, fragmentation—and a challenge to overcome.

Before the Common Era (BCE)

|

Period |

Language |

Region |

Notes |

|

ca. 1500 BCE |

Sanskrit |

Indian Subcontinent |

Vedic and liturgical texts; root of many Indian languages |

|

ca. 1000 BCE |

Classical Chinese |

China and East Asia |

Confucian texts, imperial edicts, shared scholarly tradition |

Latin: The Classical West’s Lingua Franca

Centuries later, one of the most enduring solutions to linguistic diversity emerged with the Roman Empire. Latin, first the language of Latium, became the administrative, legal, and intellectual backbone of a vast realm spanning from Britain to Mesopotamia.

Even after the fall of Rome, Latin remained the language of the Catholic Church, medieval scholarship, and European diplomacy. Universities, legal texts, and philosophical works were composed in it, making Latin a true bridge across nations and generations.

Asia’s Historical Lingua Francas: Unity Through Civilization

While European history provides well-known examples, Asia, too, developed powerful regional lingua francas—tools of cohesion across empires, religions, and trade routes.

Classical Chinese (文言文): East Asia’s Written Code

For centuries, Classical Chinese served as the written language of scholars, poets, and officials across China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Although each region spoke its own language, Classical Chinese allowed elites to communicate through a shared literary tradition. Like Latin in Europe, it enabled a pan-regional dialogue in governance and philosophy.

Sanskrit and Pali: Sacred Languages of South Asia

In South Asia, Sanskrit functioned as the language of Hindu scriptures, scientific treatises, and literary epics. It crossed regional and linguistic boundaries, influencing numerous languages from Hindi and Marathi to Khmer and Javanese. Pali, the sacred language of Theravāda Buddhism, played a similar role across Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia—preserving and spreading Buddhist teachings.

Persian: The Poetic Bureaucracy of the Islamic World

From the 10th to the 19th century, Persian served as the language of administration, court poetry, and diplomacy across Iran, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Under the Mughals, Persian was the official language of governance and the arts in India. It shaped Indo-Persian culture and deeply influenced Urdu.

Arabic: A Religious and Scholarly Standard

Though its heartland was the Middle East, Arabic extended deep into Asia through Islam. It became the religious and scholarly language of Muslim communities in South and Southeast Asia. Though rarely spoken colloquially in these regions, its liturgical and philosophical influence has endured.

Malay and Bahasa Indonesia: The Lingua Franca of Maritime Asia

In Southeast Asia, Malay—and its modern standardized form, Bahasa Indonesia—emerged as a neutral and practical lingua franca. Used for trade, diplomacy, and later national identity, it unified countless ethnic groups and languages across the archipelago. Today, Bahasa Indonesia is spoken by over 200 million people and stands as one of the world’s most successful modern unifying languages.

1st – 18th Century CE

|

Period |

Language |

Region |

Notes |

|

1st–5th CE |

Latin |

Roman Empire |

Language of law, governance, and literature |

|

3rd–9th CE |

Pali |

South & Southeast Asia |

Buddhist scriptures and monastic learning |

|

7th CE onward |

Arabic |

Middle East, later Asia & Africa |

Language of the Quran; used in religion and scholarship |

|

9th–18th CE |

Persian |

Central Asia, Iran, India |

Court and literary language across Islamic empires Dominant in diplomacy, poetry, and history |

French: The Language of Diplomacy and Culture

By the 17th century, French replaced Latin as the preferred language of diplomacy, culture, and aristocratic discourse. The influence of the French court, particularly under Louis XIV, extended across Europe. Philosophers of the Enlightenment wrote in French, and treaties such as the Treaty of Versailles (1919) were negotiated in it.

French retained its prestige well into the 20th century, often representing refinement, clarity, and intellectual sophistication.

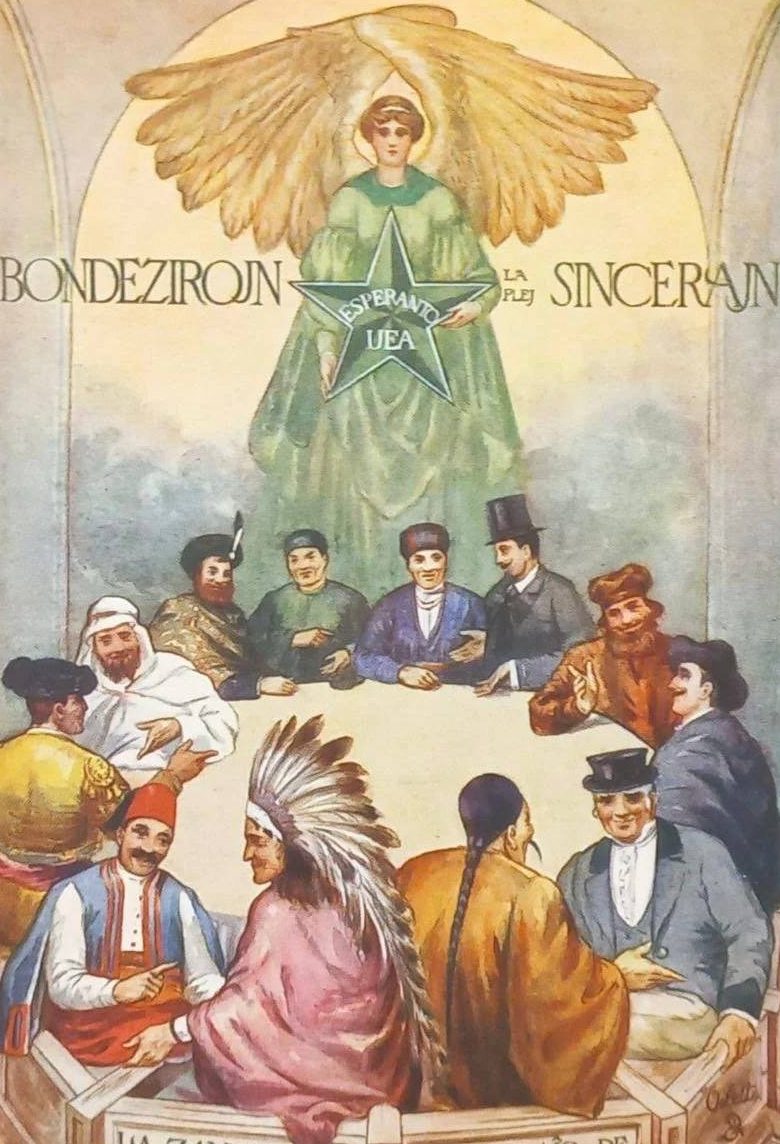

Esperanto: A Constructed Ideal

In the 19th century, the desire for a politically neutral, global auxiliary language led to the creation of Esperanto by L. L. Zamenhof. With a regular grammar and vocabulary drawn from European tongues, Esperanto was meant to foster international peace. It gained a dedicated global community but never achieved widespread institutional adoption—largely due to the momentum of natural languages tied to power and economy.

English: The Modern Global Lingua Franca

In the 20th and 21st centuries, English has become the de facto universal language—spoken by more people as a second language than as a native one. While the British Empire laid the groundwork, it was the cultural, economic, and technological dominance of the United States that globalized English.

Today, it is the language of diplomacy, business, science, aviation, and the internet. Its global reach is reinforced by its presence in education, media, and digital platforms. English’s flexibility, large vocabulary, and widespread adoption have made it the most successful natural lingua franca in history.

19th – 21st Century

|

Period |

Language |

Region |

Notes |

|

1887–present |

Esperanto |

Global (idealistic movement) |

Constructed neutral language for peace and unity |

|

20th century |

French – English |

Shift after World Wars |

English replaces French in diplomacy, aviation, science |

|

21st century |

English |

Global |

Internet, business, education, media |

Unity and the Human Voice

From Babylon’s confusion to English’s ubiquity, the story of a universal language is also the story of human aspiration—for connection, order, and understanding. Latin, Sanskrit, Classical Chinese, and Persian each played their part in shaping civilizations. Esperanto dreamed of unity. English, for now, has realized it—though not without challenges.

Yet, language is more than words—it is identity, memory, and worldview. The true universal language may never be a single tongue, but rather the shared will to understand across our differences.